A common cause of Windows Store app certification failures is a

missing or insufficient privacy policy. Many don't realize that a

network-enabled app must have a policy, or if they do, don't

realize exactly what needs to go into it. In this post, I'll talk

about some of my observations regarding what makes for a good

privacy policy for a Windows Store app.

IMPORTANT: This is neither official

guidance from Microsoft, nor legal advice from me. I'm not

a lawyer - not even close. Privacy policies are legal documents

like licenses and should be crafted by a lawyer. When you speak to

your lawyer, however, you'll be better prepared because of the

information below. These are simply my suggestions based upon what

I have observed. I do not guarantee that a privacy policy written

as I recommend will pass store certification or be an appropriate

legal document. (Hopefully that's enough disclaimer.)

Also, I am not on the Windows Store certification team. Please

don't come to me with "App X's privacy policy doesn't seem to

follow your instructions but it got in and I didn't" type of

questions. For those types of questions, there is the "Resolving

certification errors" page http://aka.ms/StoreFix and the

Windows Store support site http://aka.ms/StoreSupport .

Also, for obvious legal reasons, I cannot review your privacy

policy and provide you with feedback on it.

Yes, the disclaimer is pretty big, but there's good reason

behind that. If you dig into the certification requirements, you'll

see that we don't recommend a privacy policy or provide any

templates for one, despite it being a fairly common request. That's

because Microsoft is not able to give legal advice and, as I

mentioned above, the privacy policy is a legal document.

You should use a lawyer to help you write your privacy policy.

In reality, though, I know most independent developers will not

request the services of a lawyer, so let's talk a bit about what

should go into that policy regardless.

First, please review these requirements (specifically requirement

4.1/4.1.1). The requirements are updated quite often to remove

ambiguities and provide further guidance, so if you see any

conflicts between what I'm writing here and what's in those

requirements, the requirements rule. The other important page is

the Resolving

certification errors page which also includes information on

the privacy policy.

What is a privacy policy?

In the context of a Windows Store app, a privacy policy is a

legal document which details any privacy related aspects of the

app. It's intended to be transparent to the user and to allow them

to make informed decisions about what they share with the app, and

even if they want to install it to begin with.

ASIDE: When writing your policy, consider not

only how to explain the privacy aspects of the app, but also

whether the app even needs to the things it is using. For example,

does the server really need to store locale information about the

user? If not, go back to the app development team and request they

not keep that around. Your privacy and other legal obligations get

simpler the less you store. If you don't absolutely need it, don't

store it.

How to create a good privacy policy

A good privacy policy is clear, concise, and complete. It tells

the user exactly what is captured and what the app does it with. It

gives the user instructions to follow if they don't agree with

aspects of the policy (even if those instructions are to uninstall

the app and then email us at XYZ to delete the persisted data).

Make it specific

Many privacy policies fail in certification because the policy

isn't specific to the app. In most cases, the linked policy is a

generic one which is available on the company's web site. I

personally prefer to see a separate privacy policy just for the

app, but if that's not possible, you at least need to make sure the

policy has a section which very specifically details the named

Windows 8 app, what it collects, etc.

Any app-specific section should have its heading on-screen,

without scrolling, when displayed at 1366x768 on a PC. In this way,

an end user will more easily find the content and what an end-user

can more easily find, so can a certification tester.

Make it comprehensive

The privacy policy needs to detail every piece of information

that is captured, and what you do with it. For example:

- IP Address

- Device ID

- User name from Windows

- Language information

- Third-party account information

- Webcam? Microphone?

- Documents?

- Contact information?

- Information collected by ads? (link to privacy policy for the

ad network)

- etc.

If any of those things are transmitted (IP address always is),

then you need to say what you do with it. For example, you may

point out that your server keeps a log of IP addresses which

contact the service, but that this information is not given to

third parties, is purged every X days (if it is), and would not be

released to any third parties except when required by law. You

must

- Explain what is collected

- Tell your users how it is used, stored, secured, and (if so)

disclosed

- Provide a way for the user to control the information

- Explain how users can access the information you've

collected

- Follow the law.

Although it is rare, if you don't collect or store anything,

just say so in your policy (for example, a peer-to-peer networking

app which stores nothing, not even the IP addresses, so server logs

don't even come into play). You still need to have a privacy policy

if you declare the Internet Client, Internet Client/Server or

Private Network Client/Server capabilities.

Make it comprehensible

Legal language is generally seen as pretty opaque to common

English readers. The language serves a good purpose, however, in

that the words chosen typically have well-understood legal

definitions and therefore help remove ambiguity. A common

mistake I've seen with EULAs and similar in the past, is a lay

person writes them using what they think looks like legal language.

The end results is often both incorrect and

incomprehensible. To a lawyer, it sticks out like web page

code written by that spreadsheet guru in the accounting department

does to you.

A privacy policy does not necessarily have to be written in

legalese. (Your lawyer can help you make this distinction if

necessary). In fact, I much prefer privacy policies that are short

and understandable and written in common language. If you are not a

lawyer, and are writing your policy yourself, just write it in

plain English (or the appropriate primary language for your app)

and don't pretend to be a legal expert.

Make it honest

Be honest about what you collect and what you do with it. If

there's anything which is even remotely a gray area, explicitly

call it out in the policy.

If you update the privacy policy, include a revision date at the

top and then link to any previous versions. In general, unless

you've made the user opt in to a newer version of the policy, the

one that is in effect is the one that was out there when they

purchased the app. If there's any doubt, contact a lawyer for how

to proceed with revisions. Just don't try to slip them in there

with no notice.

Don't be mean or sneaky. It will catch up with

you.

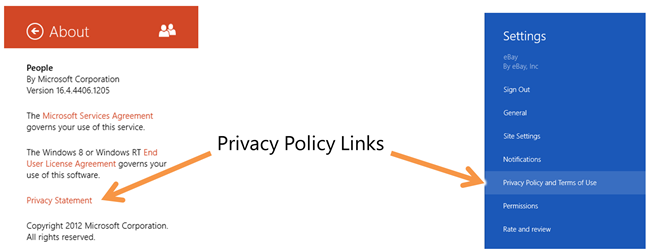

Make it available

The privacy policy is linked to from the description page of

your Windows Store app listing, as well as from the charms bar

while the app is running. I'd also encourage you to make it

available as a link from your web site's standard privacy

policy.

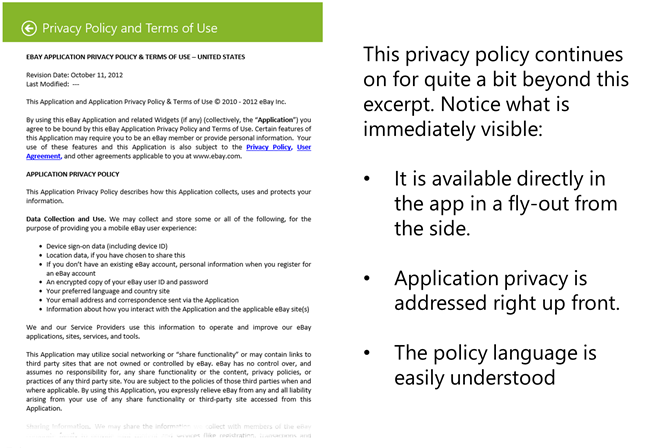

You can link to a web page with the privacy policy, or simply

include it in-line. I prefer to read it right on the screen, much

like the eBay app does, but either approach can be valid. Here's

the eBay app showing all of the points I've discussed so far.

I believe their policy is simply in an IFrame or webview in the

flyout. In that way, it is made available inside the app as well as

online.

There are many other aspects of a good privacy policy, but these

were the ones that really stood out to me. Please consider them

when creating your own apps. Most of all, consider your user and

what is appropriate for them and fair to them. Put the user in

control of their data and their privacy, and don't make it

difficult for them to opt-out.